Case Study

S-BMP-NSM-2013-002-01

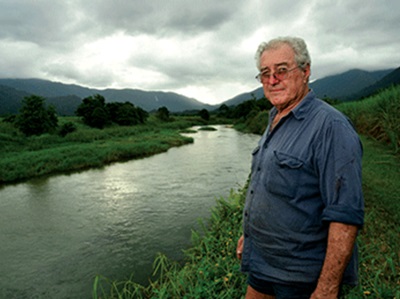

Adjoining the Babinda Creek, the Destro cane farm has used Reef Rescue funding and teamed up with the local Landcare group and Terrain NRM in projects to repair the eroded and undercut creek banks. Fixing the eroded banks and revegetating riparian zones reduces sediment loss, enhance water quality and the local environs.

High rainfall and removal of vegetation from stream banks had created scoured creek banks and highly turbid water in Babinda Creek. Bank erosion in this sub-catchment is thought to contribute one tonne of sediment per hectare per year into the Great Barrier Reef lagoon.

Stabilisation work to remediate severe erosion and resultant leaching of fine clay particulate subsoil involves battering or tapering the slope of the creek, then applying rock armour to hold the re-shaped creek bank before it is re-vegetated by Landcare with native riparian species. Mr Destro says “Once you’ve stabilised your bank you’ve always got good water, but the stuff on the banks grows too, you can grow trees or bushes which also play a part in slowing down and filtering the water.”

If previous results are any guide, the project stands a strong chance of success. Mr Destro notes that a re-vegetation site downstream that was funded via an earlier Reef Rescue catchment repair grant, has transformed in the year since the rapidly eroding creek bank was rebuilt with a similar process. Despite several floods, the majority of endemic trees planted on the re-shaped bank appear to be establishing themselves and while there is ongoing maintenance needed to keep weeds under control as the trees grow to form a canopy, the results so far are promising.

Re-vegetation of creek banks is ultimately a give-and-take affair for the grower. Tapering the creek bank in the up-coming project will mean relocating the headland 13m further away from the waterway, with the vegetation buffer on the bank acting as a sediment trap and nutrient filter. Mr Destro whose holdings span about 250 hectares says “I’ll lose a fair bit of land doing that but we’re here for the long haul.”

Fixing eroded banks and revegetating riparian zones reduces sediment loss, enhance water quality and the local environs

“The quicker the better, it’s frightening in some places down there to see what’s happening to the river.” “It involves us forking out money and that hurts, but because we want it – it is good for the property and the environment, we’ll stick our neck out. It’s paramount that we do it.”

Revegetating riparian zones and fixing eroded banks are positive steps being taken to minimise sediment and nutrient runoff and to improve the quality of water entering the Great Barrier Reef lagoon. Nowadays it’s a common sight to see tour groups of kayak adventurers paddling the upper reaches of Babinda Creek.